Few other stories in whitetail-hunting history can equal this one for sheer excitement, disappointment, and final glory. Fittingly, the buck that resulted from all this effort is in a class by itself, the one-time world record Non-Typical archery whitetail…

Surprisingly few of the top whitetails in the record book were taken by serious hunters who knew of their presence and hounded them for any substantial amount of time. However, the story of the archery world record non-typical is perhaps history’s most classic saga of a big buck hunt, even though the bow hunter who pursued the deer most fervently never got him.

This story begins back in the 1950s, along the Platte River south of Shelton, Nebraska, an area of open prairie and farmland that rolls for seemingly endless miles. Cover lies at the bottom of ravines and gullies, with most of the larger blocks of trees and brush being along the river and its major tributaries. Because of fertile soil in the bottoms, substantial crop fields also lie along this major waterway. The river is wide but fairly shallow, with much of the basin featuring islands of various shapes and sizes. Some are small, house-sized land masses, while others are more than a mile in length. Most are choked with heavy underbrush, especially willows, and some have large cottonwoods. The edge of the river itself is covered with the same types of trees and brush.

Back in 1958, rumors began to leak out about a giant buck with a “weird” rack that lived along the river and had been seen on the farm of Dan Thomas. This buck’s most relentless pursuer turned out to be Al Dawson, who had heard the rumors. At that time, Al was 31 years old and lived in Hastings, about 30 miles southeast of Shelton. He’d recently started bowhunting, and he was so taken with it that he’d totally given up deer hunting with a gun.

Dan’s farm was one Al especially enjoyed hunting, and one day during the 1958 season, he walked across a freshly cut corn field to look for deer sign. He’d stopped at a fence to look over an adjoining alfalfa field and the timbered river bottom beyond when he caught a glimpse of movement. Five or six deer had broken out of the timber and were heading straight for him.

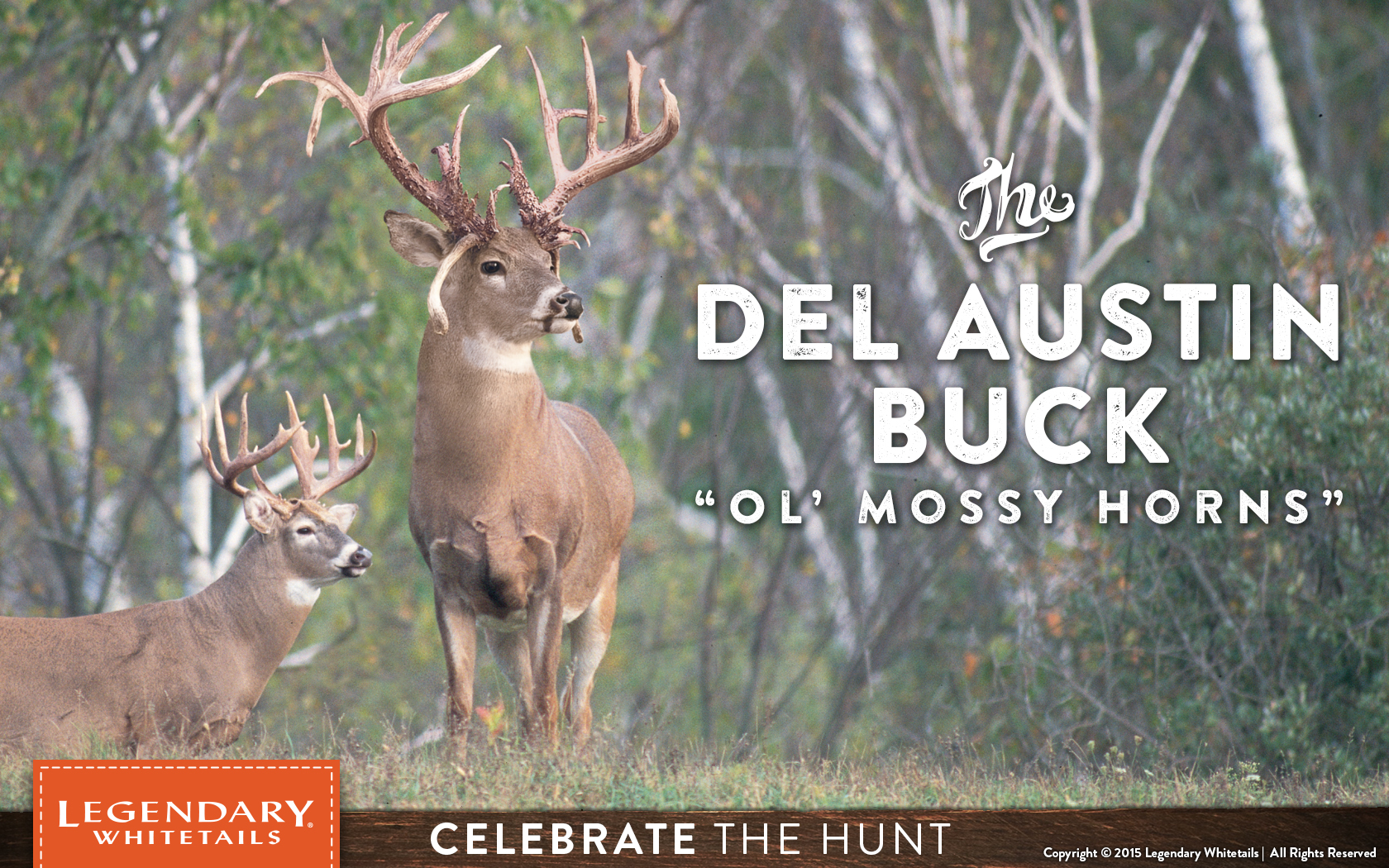

In the lead was a tremendous buck. Not only was the deer huge, with a high, massive rack, but the antlers were also the most unusual Al had ever seen. “There were heavy, scraggly points, long and short, growing from the main beams in all directions,” he said. “Strangest of all, he had these long prongs curving out and down on either side of his head, between eye and ear. They extended below his jaws, giving him an odd, lop-eared appearance.”

It appeared the deer wanted to cross the fence on the trail where Al stood. The hunter had been caught in the open, so he risked taking a couple of steps backwards, sank to one knee and nocked an arrow. By now, the non-typical and other deer had approached to within 50 or 60 yards, but suddenly, the buck swerved off to the side and cleared the fence 70 yards from Al. The monster then stopped broadside and looked directly at him. Al knew he wasn’t going to come closer, and in the heat of the moment, he decided to take a shot. Not surprisingly, the arrow fell short, and the buck whirled around and led the entire herd back to the same wooded bottom from which they’d come.

Al retrieved his arrow and followed the huge tracks across the field for some distance. He knew there would be no hope for another shot, though, so he finally left the tracks and headed back to his car. That morning, the name “Mossy Horns” came to him, as it seemed to fit that irregular set of antlers. (Today, this name is still attached to the deer.) And that same morning, the bowhunter vowed he’d keep after that buck until the great trophy was his.

Al hunted the remainder of the bow season, which ended after Christmas, and had a half-dozen chances at lesser deer. But on each occasion, the thought of Mossy Horns kept him from shooting, as he had only a single deer tag. If he waited, there was always a chance. As it turned out, he did see the huge buck twice more that season but never got a shot.

During the 1958 season, Al had hunted the buck alone. But the following year, he’d be joined by a couple of fellow archery hunters. Gene Halloran, a retired farmer, and Charley Marlowe, a Hastings advertising executive and the only member of their Oregon Trail Bowhunters Club who’d killed a deer with a bow up to that time, also would become obsessed with the hunt for Mossy Horns.

By now, Dan Thomas had his own reasons for wanting the buck dead. A couple of years earlier, he’d planted 50 young spruce trees as a windbreak about 30 yards from his house and the big buck had taken it upon himself to destroy them. In one season, he’d killed all 50 with his antlers!

In the fall of 1959, Al, Charley and Gene built tree blinds in a half-dozen locations. In those days, portable tree stands were just being developed, so their ambush sites consisted of small platforms 10 to 20 feet off the ground. Despite their best efforts, most of the archery season passed without anyone even glimpsing the huge buck. By now, the old second-guessing game had begun. Charley shot a doe, ending his season. Al finally resigned himself to the possibility that the buck had moved to another area or was dead.

Still, he kept hunting. Then, late one November evening, he saw Mossy Horns about 150 yards away, following a slough. His movement was extremely slow and cautious, and it was clear that he’d pass well out of range. Several times he stopped at the edge of thickets to test the wind and listen for danger. This was the first time Al had seen him all year, and his rack appeared nearly identical to the one he’d worn the previous season.

Finally, Al decided he had nothing to lose by trying to stalk close enough for a shot. A strong wind was blowing from the deer to the archer, and there was enough brush that Al just might be able to stay out of sight.

For a half-mile, he moved along on the most careful stalk he’d ever made. Three times the buck stopped to thrash trees with his huge rack, and each time the hunter crept closer. On two of those occasions, he was in bow range, but there was simply too much brush in the way. Finally, the buck paused at the edge of a thicket to work over another willow clump just 25 yards from Al. Two steps around a willow clump and the excited bowhunter would have an open shot. But just then, a dry twig broke underfoot and the buck was gone.

Al didn’t see him again until the final evening of the season. As the tired hunter walked out of the river bottom at dusk, realizing the buck had eluded him for another season, he noticed a dark form standing in the open. Al finally made out the white throat patch and huge antlers as the buck stood calmly, watching him from just out of range. Then, the monster turned and disappeared into the gloom, drawing the season to a fitting close.

Al muttered, “Okay, Mossy. Next year will be different.”

During the summer of 1960, Dan saw the buck about once a month, each time near his old hangout in the river bottom. The same three hunters would once again do their best to get the deer, but now a fourth had joined the quest. A warehouse manager from Hastings, Del Austin was an enthusiastic convert to bowhunting and would hunt with the group for the next three seasons.

By the time the bow opener rolled around on September 10, all four archers knew Mossy Horns was still alive and well, and everyone felt confident they had his travel pattern down cold. Stands had been built long before the season. Al had the greatest faith in one stand he’d erected near the corner of a corn field, where it joined the river bottom. Here, he had found numerous fresh tracks which he felt could belong only to the non-typical, and he resolved to hunt this spot until the great buck showed.

For seven weeks, Al sat in the stand every chance he had. Over time, he grew progressively more impatient. Then, one cool afternoon toward the end of October, two bucks stepped into the corn field about 200 yards down the fence line from the stand. They were certainly not in the class of Mossy Horns, but they were good bucks, and it had been a long dry spell. Once the deer had disappeared into the standing corn, Al climbed down and began to stalk them.

The hunter had gone only about 70 yards when, for some reason, he looked back toward his stand. Mossy Horns was standing under it! The gigantic buck stared toward Al, not sure what he was. Then the big deer caught human scent and was gone.

The following week, Charley was in his stand when four deer walked past. He, too, succumbed to temptation and arrowed a young buck, which promptly ran into the corn field and dropped. Charley had filled his deer tag for the year. But before he could even climb down, Mossy Horns stepped out of the brush and stood broadside at 30 yards!

Finally, he blew and ran back toward the river.

Near the end of that same season, Al had yet another chance at the great buck. This time his wife, Velma, was sitting in another tree about 50 yards from where Al sat. It was getting dark, and Al was almost ready to depart. Then, the snap of a twig froze him as he looked into the brush. Mossy Horns was walking slowly toward him!

Al let the buck walk beneath his stand and a short distance beyond. The bowhunter was at full draw when the buck passed, and Al shot for the front shoulder. The arrow hit with a solid thud, and the deer instantly flinched and bolted. Beneath the stand where Velma sat, a woven-wire fence was nailed to the tree. As the buck crashed away, he hit the fence so hard that the tree shook, nearly knocking Velma from her perch. But, the buck kept going.

In the poor light, Al and Velma looked for blood but found none. Finally, they decided to wait a half-hour then return with a flashlight. Al still remembers that wait as being the longest 30 minutes of his life. When they returned, they found where the buck had crashed into the fence; they even recovered the feathered end of his arrow, but it had no blood on it. Even after further searching the next day, they encountered no trace of blood or the buck.

Al was haunted the rest of the season by concern that he might have killed the deer. Had he crawled into a thicket and died, or could he have been carried away by the river, never to be seen again? During the last week of the season, Al finally filled his tag with a big 8-pointer, which was his first deer with a bow and his third whitetail ever. The season ended with no more sightings of Mossy Horns.

During the summer of 1961, Dan didn’t see the non-typical. This was unusual, as the farmer had observed the deer in each of the past three summers. Perhaps Al’s arrow really had killed the buck, or maybe he’d simply died of old age. Judging from the size of his rack back in 1958, he now was presumed to be at least eight years old.

Later, one bitterly cold afternoon near the end of the ’61 season, after the other hunters had given up, Al again was sitting in the stand from which he’d shot at Mossy Horns the previous year. Just before dark, he spotted a button buck making his way through the willows about 100 yards off. Following him was a large buck, and behind that buck was the one whitetail Al had expected never to see again—Mossy Horns!

Suddenly, the season took on an entirely new dimension. The giant moved as cautiously as ever while he worked his great rack through the willow bushes. His rack looked the same as before, and if anything, even bigger. Despite the cold, Al began to sweat.

Before dark, the two other bucks headed out into the field, but Mossy Horns remained in the willows. Then, a half-dozen does came out under Al’s stand and began feeding. Soon, two younger bucks joined them, and all eight milled around near the stand until dark. Mossy Horns finally entered the field just before dark, but he would come nowhere near Al’s tree. It was as if he remembered the shot from a year earlier —and he probably did.

In the spring of 1962, Dan had the good fortune to find a matching pair of shed antlers from Mossy Horns, not far from where the guys had been hunting the buck. Now, it was clear that the buck was as big as Al had always claimed. (Charley was the only other hunter in Al’s group who’d even seen the buck in four years!) Al had believed Mossy Horns was a new archery world record, but he’d had no proof. The evidence now was in hand.

The giant sheds had an 11-inch drop point off one base and one of 13 inches off the other base. Approximating the inside spread, the rack would have scored in excess of 281 non-typical points, easily making this buck just what Al had claimed—a Pope and Young world record.

As it turned out, the sheds probably were from the previous year—the ’60 hunting season—which was the year Al thought he had hit the buck. Near the end of one of the long, club-like drop-tines off the bases was what appeared to be a three-edged broadhead mark that had penetrated the antler about a half-inch! Instead of the arrow hitting the shoulder, as had been intended, it apparently had hit that antler tip! This would account for the buck’s excessive crashing and hitting the fence, as he was temporarily stunned from the shock.

In 1962, Al’s fifth season of hunting Mossy Horns, he decided to try a new tactic. For weeks in the summer, the archer cut trails through the heavy brush in places where he’d seen the buck most often. At the most likely crossings, he built tree stands. Then, starting a full month before bow season, Al kept away from the area to allow Mossy Horns time to get used to the changes. Once again, no one saw the old buck prior to the season.

At the time, Interstate 80 was being built on the north side of the bottoms where Mossy Horns lived. As a result, the Platte had been temporarily dammed upstream. One day early in the season, as Al walked the dry river bed, he found the fresh, unmistakable tracks of the non-typical. From the looks of it, the buck had been traveling to an alfalfa field. Al backtracked to a small island choked with willows, where he jumped the deer at close range. His rack looked just as big as ever.

During the next few days, Al was careful to keep away from the island and the primary trails the buck was using. One evening, while he sat in a tree where a runway crossed a big slough, several does walked under his stand, followed by an 8-point buck that stopped to rub his antlers on a bush. Mossy Horns showed up just after the smaller buck, but eventually moved off without coming close enough for a shot. That same week, Al had one more distant look at him.

The following week the monster wasn’t seen, so Al searched the dry river bed again to find out what he was doing. Here, the bowhunter found a trail the buck hadn’t been using previously. Early bow season was drawing to an end, so Al decided to set up a new stand as a last-ditch effort. A nine-day rifle season would begin soon, and too many other local hunters knew of the legendary deer. He’d be lucky to survive the onslaught.

On Al’s first evening in the new blind, an hour before dark, he saw the great buck slip out of the willows on an island and head his way. Mossy Horns crossed the dry channel and walked to within 15 yards of Al’s stand. It appeared it was all over but the shot.

But as always before, something went wrong: The buck stopped in heavy brush. Finally, the buck circled the tree at 20 yards, but he never left the brush for a clear shot. He locked up not 20 feet from Al’s stand, where a fence came down to the river, but there was no chance to draw. After another 10 agonizing minutes, Mossy Horns jumped the fence and walked into the alfalfa field. He stopped broadside at 45 yards …and Al sent an arrow just over his back.

The last afternoon in October rolled around, and the early bow season was about to end. Al and Gene got to the bottoms early and chose their stands. Del and Charley left Hastings after work and hurried out to the farm to get in a last-minute hunt.

Originally, Del had planned to sit in one of Al’s stands but now feared he wouldn’t be able to find it quickly. So, he brought along a portable platform and placed it on a large island of thick brush and liberally sprinkled buck lure on the ground all around his tree.

Del stood on the platform until just before dark; then, as he was starting to get down, a loud crash from upwind caught his attention. It was hard to see antlers in the dim light and heavy cover, but the hunter could tell the buck was big. For some reason, he ran toward Del and stopped 20 yards from his tree, turning almost broadside. The archer drew his 45-pound Oneida recurve and drove a Bear Razorhead behind the shoulder of the deer, which promptly bolted.

Al and the other hunters waited for Del until an hour after dark, but still there was no sign of him. Finally, with flashlights, they headed toward the river and met him halfway. He relayed his story, noting that he wasn’t sure if the deer he’d shot was Mossy Horns or another buck.

From the blood, it appeared Del had made a hard hit. After some searching, they found the broken arrow, which had been snapped off 10 inches above the head. For three hours, the hunters trailed the buck through slough grass and willow thickets until the blood and their flashlights were nearly gone. They decided it would be best to wait until daylight to continue the search.

The next morning, within 100 yards of where they had stopped the previous evening, they found the buck lying dead in a clump of willows. He was indeed Mossy Horns! It was a bittersweet moment for Al Dawson. The five-year quest had ended with someone else taking “his” buck. On the other hand, one of his buddies had been fortunate, and that was reason enough to celebrate.

Mossy Horns was showing signs of age. He had no fat on his body, and his loins were sunken. Even so, he dressed 240 pounds, and Al felt sure he would have been 60 pounds heavier during earlier years. The rack wasn’t quite as massive as it had been earlier, but it still scored 279 7/8 points when measured by P&Y’s Glenn St. Charles. At the time, this buck was the second largest non-typical in the world (behind only the 286-point Jeff Benson Buck from Texas), and Mossy Horns was far and away the new world record by bow. This buck is indeed a fitting archery world record, and even after all of these years, he’s faced no serious challenges to that title.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this story is what it tells us about the lifestyle of a monster buck. Rarely is there any account through which we can get to know a deer of this caliber and see how he avoids dangers time after time. Despite being subjected to serious hunting pressure, this giant came within minutes, perhaps seconds, that fateful afternoon of perhaps surviving to die of old age. Can you imagine how seldom Mossy Horns would have been seen by casual hunters who didn’t know he even existed?

With a Non-Typical Pope & Young score of 279 7/8, it still ranks as number two archery of all time. This buck is truly fitting as one of the greatest hunter versus whitetail stories ever recorded.